Long COVID & the Ears: What you need to know about tinnitus, balance, and hearing

This article provides an overview of the ear structure and how COVID can affect hearing, tinnitus, and balance, along with practicle information on steps you can take to manage symptom flare ups.

Updated January 7, 2025

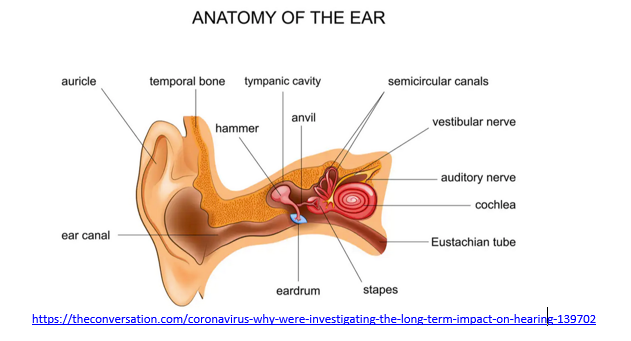

There are a growing number of sensory deficits associated with COVID-19 being researched as we learn more about the acute and chronic health impact of this virus. Symptoms include tinnitus (ringing in the ears), balance issues, trouble hearing, ear pain, sensation of clogged ears and in some cases, auditory hallucinations (hearing voices). Some of these symptoms can easily be confused for other conditions. For example, ear infection (pain, decreased hearing) or schizophrenia (hearing voices) can also be the result of auditory nerve inflammation.

When COVID-19 causes multisystem inflammation syndrome (MIS, MIS-C, MIS-A), many people experience inflammation of the central nervous system. It is important to have an Ear, Nose and Throat doctor (ENT) check your ears for disease if you are experiencing any of these symptoms. When doctors can't find anything wrong, it's time to consider inflammation of the auditory nerve and possibly other cranial nerves, including the trigeminal nerve that wraps around your face. We do not have the technology to look at nerve inflammation, so diagnosis is made by the process of elimination, and ruling out other major health issues like infection, injury or tumor. Complications from nerve inflammation can be permanent in severe cases, but most often they are temporary. Symptoms can also be exacerbated by things like stress, allergic reaction, histamine release and foods/drinks.

COVID-19 research

Researchers identified ten COVID-19 patients with audiovestibular symptoms such as hearing loss, vestibular dysfunction and tinnitus to investigate the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and audiovestibular dysfunction. They found mechanical (ear structure and functional aspect) issues that explain the issue with COVID-19 patients and infectious ear related diseases. Researchers also found that COVID-19 can cause new-onset hearing loss, tinnitus and/or dizziness caused by of infectious inner ear disease.

Key findings

Human and mouse inner ear cells are vulnerable and can allow SARS-CoV-2 viral entry, similar to the eyes, nose and mouth. They also found that SARS-CoV-2 can infect specific human inner ear cell types, meaning that inner ear infection may cause COVID-19 associated problems with hearing and balance. The link to the full research article is listed in the resources section.

This study shows that COVID-19 can infect the inner ear and may cause hearing and balance symptoms by affecting the Schwann cells and hairs cells of the inner ear.

"Vestibular hair cells serve as sensory receptors in the inner ear that function to assess and monitor head motion, a sense of balance, allowing humans and animals to orient themselves," stated Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York.

Schwann cells are found in the inner ear known as the cochlea are vital to hearing. The vestibular hair cells and Schwann cells express proteins that are essential for SARS-CoV-2 to enter cells. The ACE2 receptors located on the surface of these cells have enzymes that allow COVID-19 to attach to these cells.

The study did not indicate whether these issuers are permanent or temporary, however, based on what we know about nerve inflammation, we can anticipate full or partial improvement in symptoms with some lifestyle changes and interventions.

COVID and the ears

Covid-19 spreads through aerosolized droplets when a sick person coughs, sneezes or releases saliva when they talk, yell or sing and someone inhales the droplets. The droplets can also land on a nearby surface that can be picked up by touching the surface (like a restaurant table or door handle), then touching mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, or eyes.

COVID-19 cannot infect you through the outer ear, the part that you can see plus the ear canal, because it is not a mucus membrane. The outer ear blocks germs, like viruses and bacteria, from getting inside. And ear wax is a physical barrier and contains some chemicals that help kill germs while hair in and around the outer ear can trap germs. The eardrum, also known as the tympanic membrane, creates another barrier between your outer ear and the middle ear, the part of the ear behind the eardrum. Ear infections happen in the middle ear. Those germs travel upward from the nose and mouth, through the Eustachian tube, to the ear.

If you've been checked out and nothing is medically wrong, it’s time to consider what you can do at home.

Tinnitus (ringing in the ears) is very common in Long COVID. It is triggered by foods, alcohol, smoking, over exertion, lack of sleep, and physical or mental stress, and there are things you can do to reduce the symptoms.

Things you can do to help reduce symptoms

Look at a low histamine, low sugar diet to reduce inflammation.

Start a food-symptom-activity journal to identify symptom triggers. Gluten/wheat, soy, dairy, alcohol, smoked and fermented foods, preservatives, smoking/vaping and sugar are all common triggers.

Talk to your doctor about antihistamines to reduce the mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS).

MCAS causes histamine overproduction leading to inflammation of the nerves and organs.

Consider chiropractic if your neck seems stiff or you are having limited range of motion looking sideways.

Myofascial inflammation / swelling may be putting pressure on the area. Massage, acupuncture, or acupressure (for ears) may help with nerve inflammation.

Gentle massage of any tender and puffy areas along the front, at the bottom of your ears near your jaw and on your ear itself, including the lobe.

Sinus pressure can make your ears feel "stuffed up" or cause headaches, ear pain and painful throbbing around your temples. For centuries, acupressure and massage have been used as a remedy for pain and pressure in your ears and head.

Acupressure is an alternative medicine technique based on certain "energy points" on your body. There's evidence to suggest that acupressure can be used to treat health conditions of the sinus area and ear canal. The pressure points on your ear are called the "auricular points."

Acupressure involves putting pressure on the same areas where an acupuncture needle would be inserted. This would indicate that pressure points on parts of your body that aren't in pain can treat and relieve the symptoms of headaches and earaches. Keep reading to find out what we know about acupressure and holistic medicine.

Things you can do to help yourself

Minimizing physical & psychological stressors is essential in recovery from Long COVID.

Nutrition: Try to eat protein and fresh vitamin rich foods daily and avoid chemicals, preservatives, sugars, fast foods, prepared foods and high histamine foods.

Don’t skip meals. Your body needs protein, vitamin C, and vitamin D to heal from any injury or illness. A low histamine or low carbohydrate (sugar) diet is recommended by doctors treating Long COVID (PASC), and many people report a reduction in symptoms within 1-3 days of the diet change, including decreases in sneezing, itching or hives, irritable bowel syndrome, body pain, along with a reduction in swelling and inflammation.Hydration: A minimum of eight 8 oz glasses of plain water daily is recommended.

Avoid drinks with chemical additives. You can easily make a fresh electrolyte drink yourself by adding a dash of mineral rich Epsom salt and a piece a fruit like a raspberry for flavor instead of spending money on commercial drinks like Gatorade that contain chemicals and sit in plastic bottles for long periods of time. Remember that caffeine and alcohol have dehydrating effects.Sleep hygiene: Getting 7-9 hours of sleep so your body can repair itself.

You need at least 4 hours of uninterrupted sleep to get into the restorative phase of sleep.

Avoid stimulating activities after dinner like thrilling movies or books, arguments, negative news or frustrating stimuli.

If you wake up frequently or with a startle, you may be experiencing drops in your oxygen level, which signal your brain to release adrenaline to force you to take a breath. This could be a temporary inflammation issue or more enduring sleep apnea. Ask your doctor for a sleep study to evaluate your need for a CPAP or BiPAP, a machine that pushes air into your lungs when it senses an apneic episode (periods of not breathing).Stress management: Stress affects every component of your life.

The only thing you can control about stress is your reaction to it. Try to avoid or minimize your exposure to stressful situations: Turn off the news, make family visits that end unpleasantly short, wait for the morning to have intense discussions, let go of things that annoy you but don’t really matter in the big scheme of things, avoid intense conversations or entertainment in the evening.

Exercise within tolerance: Pace yourself and do not push your body to extremes in any way.

For some this may mean seated breathing exercises, walking to the mailbox. Rest when your body says to slow down. Gradually build on your activity endurance as your body cues you to progress. This can be hard to gauge, because when you feel good you naturally do more, but if you do too much you may experience symptom flare ups 1-3 days later as the post exertion inflammation builds. Some people describe this as post exertional malaise, others experience severe recovery setbacks.

Breathwork: You can literally stop the fight or flight reaction by taking slow deep breaths.

Deep slow breathing shuts down the adrenaline flow, slows your heart rate, lowers your blood pressure and decreases stress related histamine release. When you do this, your blood reroutes back to your brain and nervous system to allow you to think clearly. It also allows your body to use its energy and oxygen to heal your inflamed nerves and organs.

ProMedView Nurse Coaches - We get it.

Our clinical experts advocate for those with Long COVID.

Individual coaching

Group Q&A sessions

Peer support groups

Educational webinars

Keep moving, keep breathing.

COVID Care Group, LLC is not a healthcare provider and does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.CCG is not a “not for profit. Membership fees, donations and gifts are not tax deductible.

Article resources

Why COVID-19 Can Affect the Inner Ear and What that Means for People with Long COVID

Audiovestibular Symptoms in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases - NIH

Audiovestibular symptoms and sequelae in COVID-19 patients - NIH

Cranial nerve involvement in COVID-19

Overview of the Cranial Nerves

https://www.greatbigcanvas.com/view/the-physiology-of-balance,2280167/

The physiology of balance: vestibular function

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome: Proposed Diagnostic Criteria - NIH

How to Relieve Pressure in the Ears From Sinus Drainage

Originally posted November 20, 2021